Image: Organ Mountains Desert Peaks, New Mexico. Photo by Lisa Phillips, Bureau of Land Management, Las Cruces District Rangeland Management via Wikimedia

So many stories surround Taos, New Mexico, I felt a bit trembly when Highway 518 emerged from the evergreen Carson National forest and looped down into the remote New Mexico valley. According to legend, people who enter Taos are destined to remain there forever… or else become so restless that they can’t be content anywhere else.

But as the wide Paseo del Pueblo Sur carried me into the village, I could shrug off my jitters. The bustling plaza was a sea of tie-dye T-shirts. Outside the adobe McDonald’s, an art festival was in full swing. I stopped to buy earrings shaped like UFOs. I could leave any time I wanted.

I simply didn’t want to yet…

“Mystery Mountain” Lures Artists to New Mexico

“When the mountain wants you, you will stay,” warned a woman with silvery hair. She was from Texas, but the mountain had wanted her, and suddenly here she was at the festival where her husband – whom the mountain also wanted – had won a prize for his birch panel designs. When good fortunes such as this happen, “you know.” She tapped her heart. “You know in here.”

Only 4,700 people live in Taos, but some 1,336 of them are artists. Everywhere I went, there they were: Painting murals on garbage dumpsters, teaching creativity workshops at the Mabel Dodge Luhan House, pouring cranberry punch at gallery openings, holding up the checkout lines at Wal-Mart as they chatted about the quality of the light.

There’s a strange intensity to the light in the mountains surrounding Taos. It radiates an eerie psychic energy, illuminating alien rock formations and vast red landscapes. And then there’s that legendary, mysterious hum, said to come from a hidden government laboratory. Anyone who hears it is never quite the same. Cardiologists enroll in past life therapy. Stockbrokers discover a talent for macramé. High school business teachers post desperate messages on the bulletin board at the Super Save: “Wanted – Studio apartment for quiet sculptor.”

Many of the people who live in Taos never actually planned to. They were just passing through, visiting a friend, heading for some other destination, when the mountain reached out and grabbed them. Gathering at Sheva Cafe, they shake their heads in wonderment. How did it happen?

“It hit me like a brick wall,” says Bill Davis, a photographer who arrived in 1969.

“I was captured… Taos chose me,” says Susan Ammann, who left Wall Street to make pots in an adobe studio.

“I came to buy an RV park,” says Rhode Island native Phoebe M. Sullins. Surprisingly, mysteriously, she stayed to become a painter.

Kyle Morgan, also a painter, grew up in Taos, but left. “I had to come back,” she explains. “I kept having dreams about the mountain, the Pueblo.”

Again and again artists speak of this magic, telling stories so polished and practiced they take on the luster of a fairy tale. Sometimes voices are quiet, reverential, and sometimes a bit too earnest, as though the tellers are trying to convince themselves that the tales are true.

By my third day in Taos, I was lingering in real estate offices. I had my eye on a cozy pueblo with a bright blue door. Then, half-way seduced, I began to hear rumblings.

“The idea of Taos as a paradise is a myth,” says Anita Rodriguez, painter and activist in the Hispanic community. According to Rodriguez, the utopian promise comes true only for a select – mostly Anglo – minority. “The culture that first drew artists to Taos were the Indian and Hispanic cultures,” says Rodriguez. “Yet, until five years ago, it was nearly impossible for a Hispanic artist to be represented by a Taos gallery.”

Native Americans have voiced similar complaints.

“My grandfather gave his pieces away not knowing how much they are worth,” says Carlos Barela, a woodcarver. “That’s not going to happen again. I’m not going to sell my work cheap.”

Of course, the predominately Anglo galleries have recognized some Hispanic and Native American artists. John Suazo, who grew up in Taos Pueblo, is renown for his simple, evocative sculptures inspired by pre-Columbian culture. However, art forms most often practiced by native groups – pottery, jewelry, textiles, and religious works – are frequently overlooked. Moreover, many Native American and Hispanic artists do not have the business training necessary to attract galleries or to aggressively market their work.

The result? Isolated groups of creative people who produce quantities of beautiful and meaningful work, yet know little about each other. “This community,” says Anita Rodriguez, “is ghettoized.”

Meanwhile, the longing for paradise continues to lure artists and free spirits from California, New York, and other far-flung places.

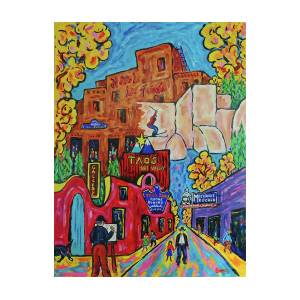

Image: Taos Fall Colors, Painting by Bill Binger, Fine Art America

Rents have skyrocketed, and bulletin boards at book stores and coffee houses are papered with desperate messages: “Wanted – Studio apartment or room for quiet painter” (or “sculptor,” or “composer,” or “poet”). At the adobe McDonald’s, locals grumble that Taos is getting too big, that tourists have taken over the Plaza. And, amidst howls of protest, Eya Fechin, daughter of the famed painter Nicolai Fechin, has constructed an 85-room inn behind her father’s secluded Taos home.

Rebelling against these forces, a group of mostly-young artists have formed a collaborative in Arroyo Seco, a tiny, mountainside village five miles uphill from Taos. The artists display avant garde works, perform improvisational theater, and stage 60’s style “happenings” in a two-room house called the Art Lab. Just up the road, Barbara Waters, widow of Taos writer Frank Waters, is resisting pressure to sell their acreage to real estate developers. Instead, the land will be used as a haven for writers and artists.

So, it seems, paradise isn’t found, it’s created: It’s made by going out into the wilderness, turning away from all that is trendy and sure, listening for whatever messages might blow in from the hills, joining forces with fellow seekers, and sinking down roots in uncharted territories. Ironically, the most earnest efforts to create paradise often destroy it. But true believers persist, weaving wishes like a Navajo blanket, forming colorful and comforting myths of magic and healing.

Learning this made it possible for me to leave Taos. As my rental car climbed Route 68 toward Pilar, I felt a tug, as though I was pushing through the membrane of a dream. Then, my spirit soared and I drove – a bit too fast – past red cliffs and frosted mountains. If they called out to me, I did not listen. The spell was broken.

Or so I thought…

Upon my return home, I did something unexpected. I packed my belongings and moved out of my apartment. I didn’t go far – I simply moved to an upper floor in the same building. But, like Taos, the elevation is high and the light is brilliant. I’m hanging prints by Taos artists Carlos Hall, Tom Noble, and – yes – R.C. Gorman. I’m doing guided meditations. I’m pretending that I never left.

Adapted from The Tao of Taos by Jackie Craven, previously published in the Providence Sunday Journal and other newspapers. Inquire about reprint rights.

SHARE THIS PAGE

I visited Taos several times in 1983. I went skiing in the winter, at several times at a restaurant – Charlie’s? – and acquired one piece of pottery that I love, and I wanted to find the artist, the piece is kind of “folded”, part of a tea set – I could only afford one cup – but it reminded me more of a Japanese set, since there were 5 teacups & a teapot. The cup – more of a “glass” is signed JW ’82 – any idea who the artist might be?

Thanks – PS I moved back to Portland, Oregon, my native land, in late 1983. But Taos still beckons – I fell in love with New Mexico, and if I ever got a chance to choose, I’d move back there.